The Day That Science Won

The Day That Science Won

— Mike Mangiaracina

The first day of school is usually a day of small moments. Teachers work hard to manage each transition, knowing that an overabundance of control now will pay dividends for the rest of the year. Procedures are established, classroom routines practiced. It’s not a day for unstructured activity or too much exuberance.

But this year was something different. No less an authority than the solar system intervened to add some mischief to our first day of school.

As the science teacher, I had been planning for this day for months. I felt a special obligation to my school because I knew that the solar eclipse would be a very special event. Everyone was expecting me to do something and I didn’t want to disappoint. I rounded up hundreds of pairs of eclipse glasses, packets of materials from NASA, and instructions for pinhole viewers. At our in-service faculty meetings, my daily announcements became predictable fixtures of our time together.

Not that everyone was as excited as I was. There was some grumbling about the timing, and most people didn’t really know what to expect. Our school district came across as particularly unenthused. The best they could do was issue a statement that read, in part, “Schools are permitted to participate in this event if the viewing is tied to a specific educational lesson.”

The message was clear. Just going outside to view the eclipse wasn’t going to be good enough. But if there was a worksheet involved, then it would be okay.

I’ve seen this kind of attitude before from the powers that be, and I wasn’t having any of it. We would certainly be teaching our students about orbits and shadows, but those lessons wouldn’t make or break the experience. Sometimes the phenomenon itself can be enough, and just experiencing wonder together can be an “educational lesson.” The seeds we plant in school often bear unexpected sprouts, and seeds of wonder don’t get much better than an eclipse.

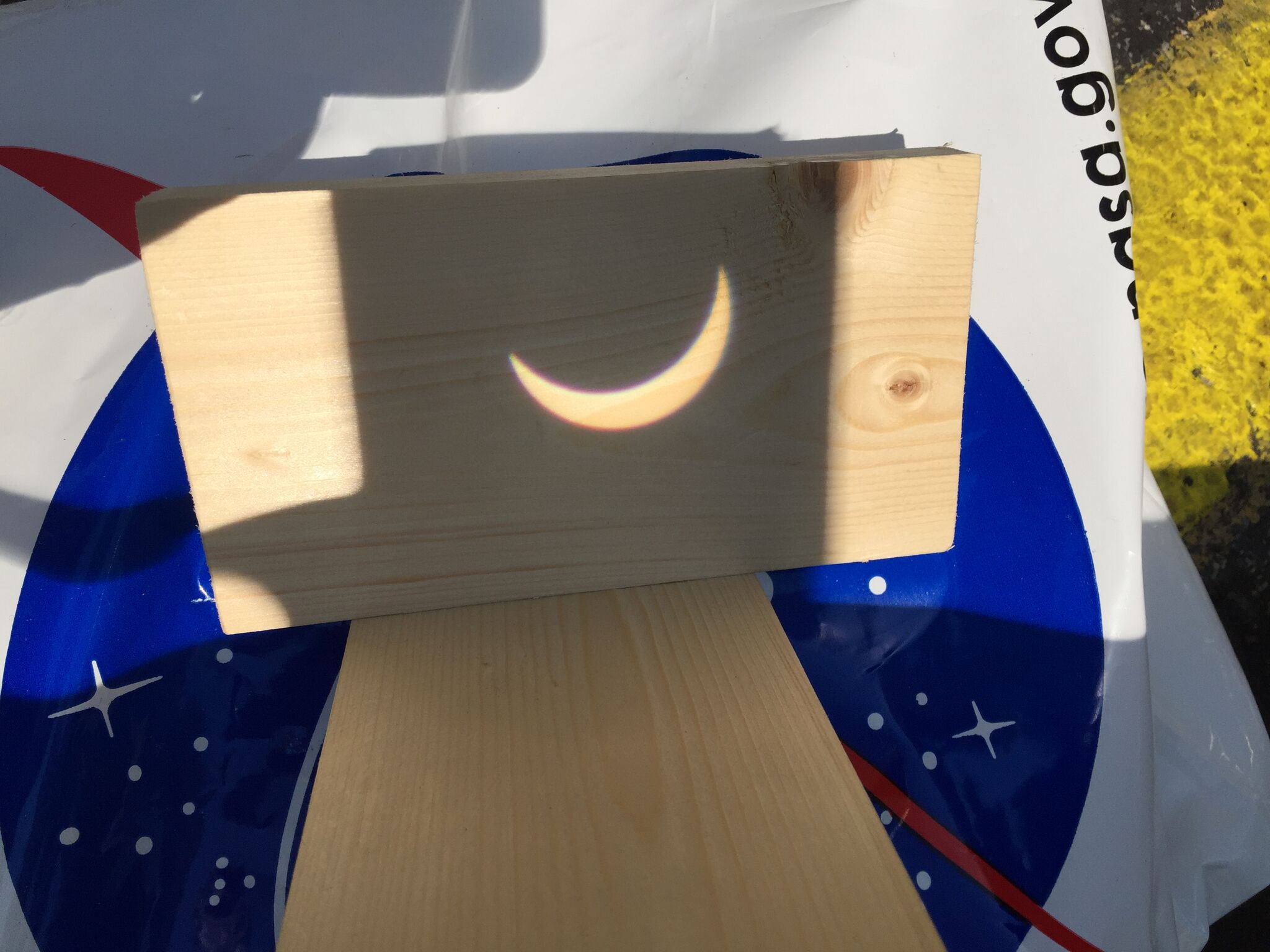

I was the first one on the playground at 1:17, when Washington D.C.’s eclipse began, on its way to 81% of totality an hour and a half later. I set up my projector which focused the sun into a 2 inch circle of light on a wooden view screen. Looking closely, I saw that the circle had a tiny notch taken out of it on the upper right. It was happening! Although I was expecting this for months, nothing prepared me for how excited I was to see this with my own eyes.

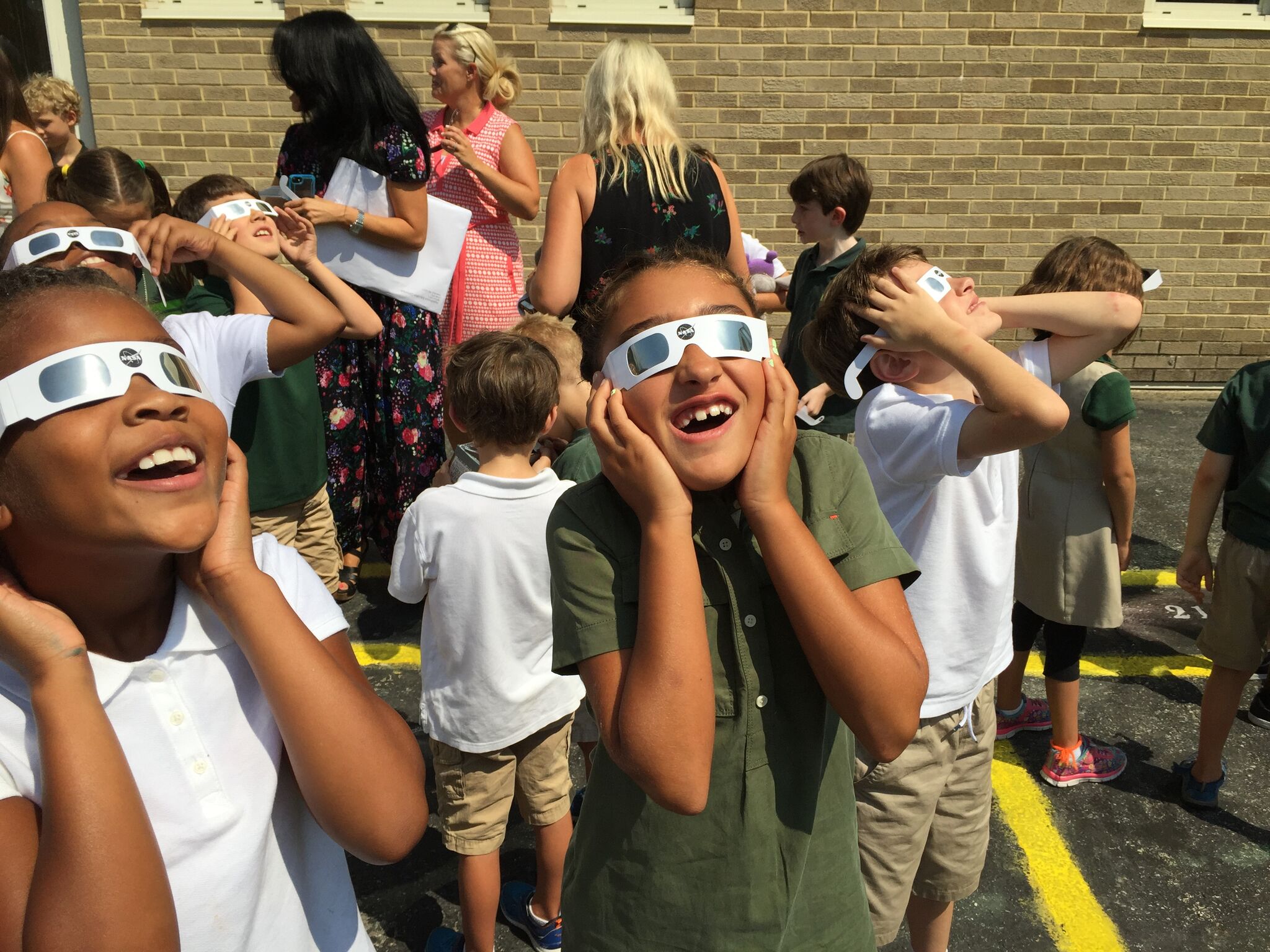

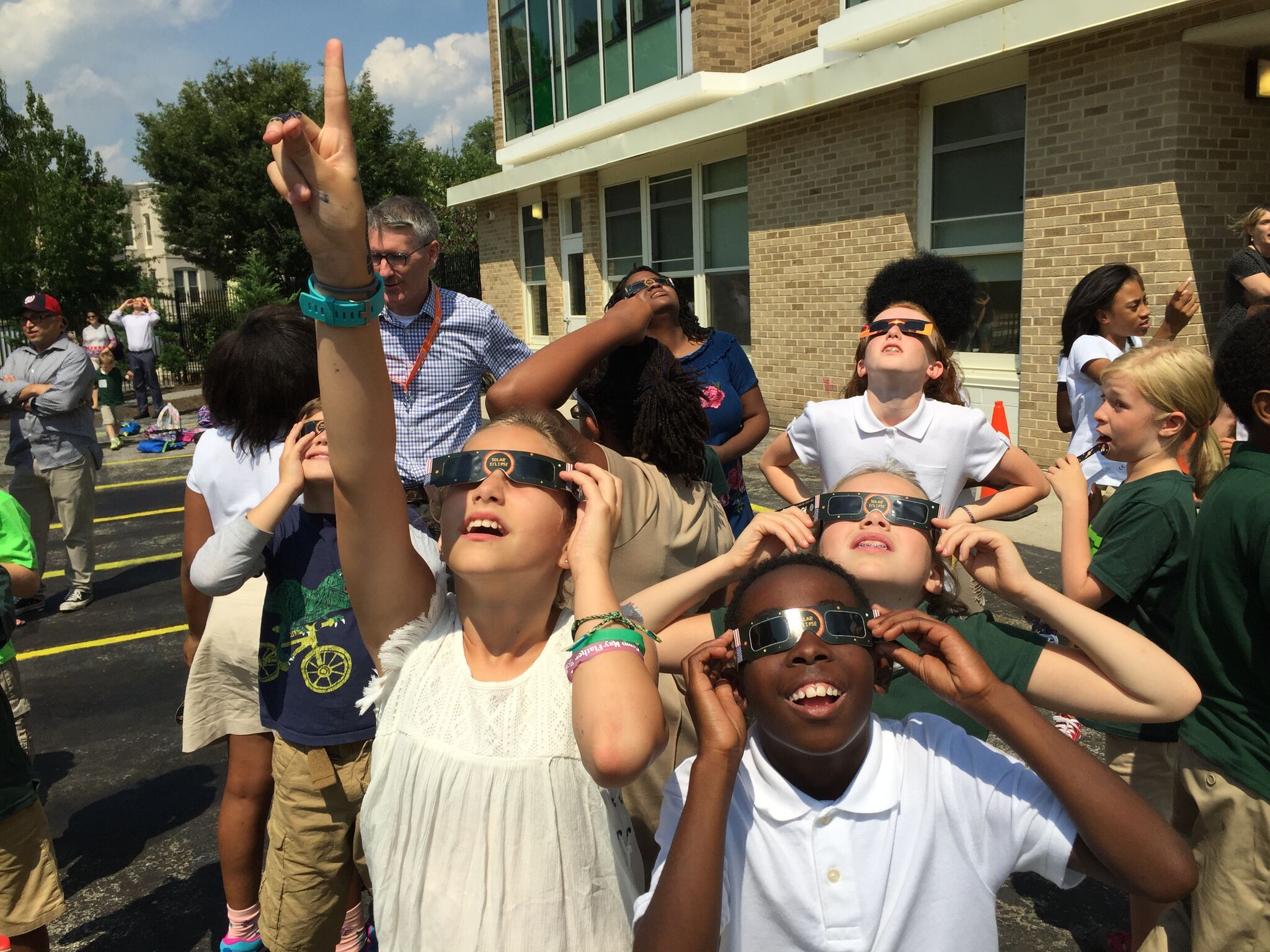

Stude nts, teachers, and parents started trickling out of the building, putting on their eclipse glasses and looking up. One by one, I saw the same dazzled elated look emerge on everyone’s face, adults and children alike. People pointed and shouted, and everyone smiled from ear to ear. I’ve seen some amazing things, but I’ve never seen so many people share so much joy from looking up into the sky.

nts, teachers, and parents started trickling out of the building, putting on their eclipse glasses and looking up. One by one, I saw the same dazzled elated look emerge on everyone’s face, adults and children alike. People pointed and shouted, and everyone smiled from ear to ear. I’ve seen some amazing things, but I’ve never seen so many people share so much joy from looking up into the sky.

The playground became host to a big party, with hundreds of families  coming and going. We looked into cereal box pinhole viewers and made little projections of the crescent sun with colanders or our hands. Students gathered around my projector and watched as the shadow of the moon progressed across the shrinking disc of the sun. When the eclipse reached its peak at 2:41 most of the school was outside looking up.

coming and going. We looked into cereal box pinhole viewers and made little projections of the crescent sun with colanders or our hands. Students gathered around my projector and watched as the shadow of the moon progressed across the shrinking disc of the sun. When the eclipse reached its peak at 2:41 most of the school was outside looking up.

I was lucky enough to be standing next to my principal as she put on her glasses and looked up. Earlier, I may have heard her mention that the first day of school was not the best time to have an eclipse, but now the moment of truth was here. “This is a lot cooler than I thought it would be,” she said, her voice animated. That summed it up for me. If you want to teach science, nothing beats a great phenomenon, and they don’t come much greater than a solar eclipse.

I couldn’t help but think of what a welcome relief this day was for our school, and for the whole country. At a time when we can take our pick of awful things to focus on, we finally had something to unite us. On this day, at least, there would be good news.

I took great pleasure knowing that in these divided times, science was uniting us. There were no eclipse skeptics stepping forward to tell us that this wasn’t happening, or that astronomers were shifty and untrustworthy. Today, I thought, science won.

No matter how bad it gets, we still have the sun and the moon and I hope that the joy we got from that great day holds on a little longer. From millions of young students across the country, I think we may just see a little more wonder, and a few more budding scientists.

gets, we still have the sun and the moon and I hope that the joy we got from that great day holds on a little longer. From millions of young students across the country, I think we may just see a little more wonder, and a few more budding scientists.

This is the 4th post from Mike Mangiaracina’s “Learning to Wonder” series. In the series, Mike, an elementary-school science teacher, reflects on the many connections that can be found within his classroom, between teachers, students, and their shared world. The stories shared here come from the unique look into students’ lives that an elementary science classroom provides.

This is the 4th post from Mike Mangiaracina’s “Learning to Wonder” series. In the series, Mike, an elementary-school science teacher, reflects on the many connections that can be found within his classroom, between teachers, students, and their shared world. The stories shared here come from the unique look into students’ lives that an elementary science classroom provides.

In case you missed them, here are Mike’s first three posts The Poetry of Phenomena, Come On In, We’re Daydreaming! and Back to School. Be sure to check back each month for Mike’s Learning to Wonder posts!

Leave a Comment