This morning, I heard on the radio that today is Madeleine Albright’s birthday. I can think of no better way to celebrate her birthday and honor her life and leadership than sharing her words with you.

This morning, I heard on the radio that today is Madeleine Albright’s birthday. I can think of no better way to celebrate her birthday and honor her life and leadership than sharing her words with you.

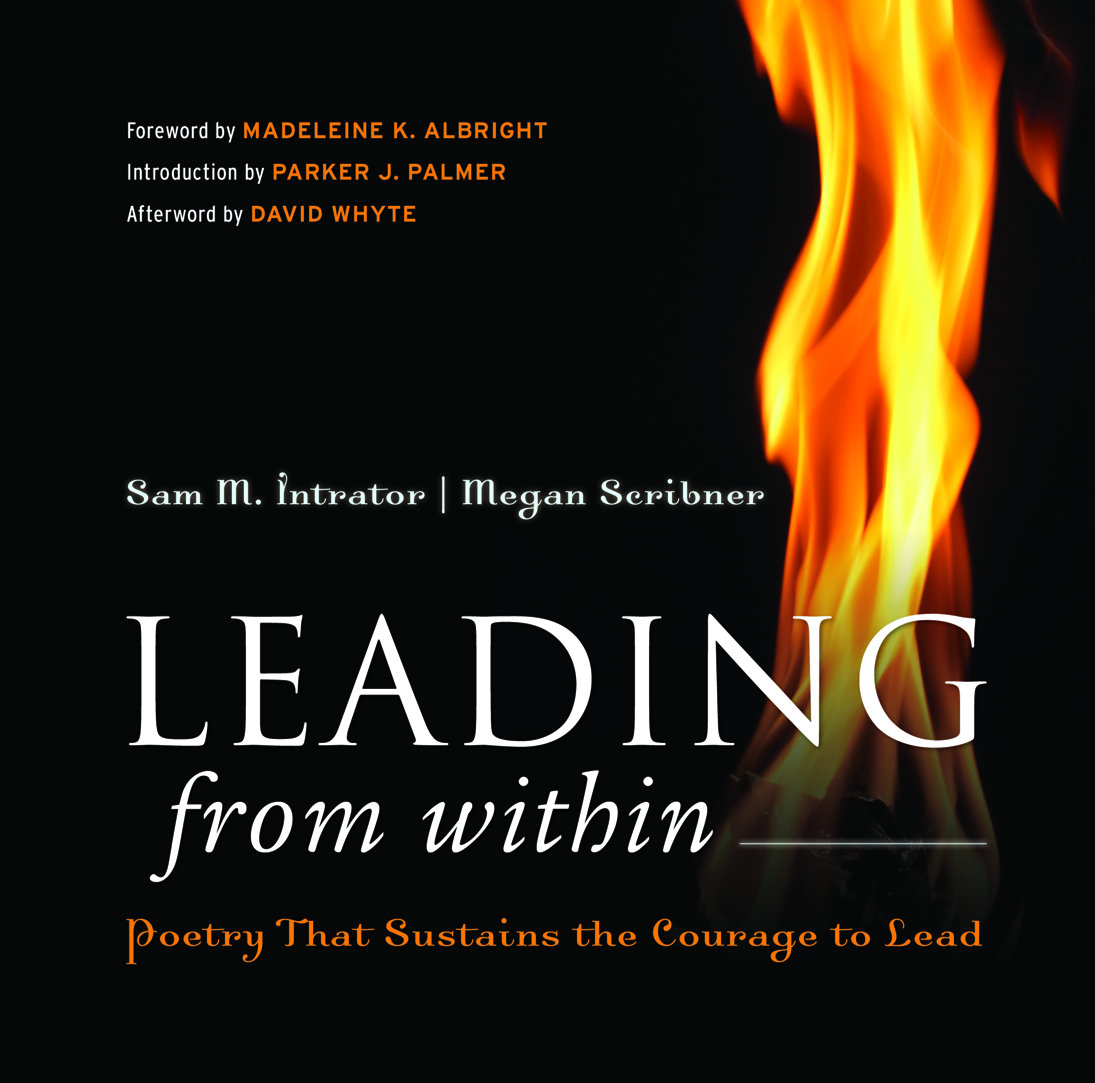

Back in 2007, she wrote the Foreword to our book, Leading From Within. I remember that when I first read her words, I was brought to tears. As I read them again this morning, they had the same effect. In fact, her words and wisdom seem even more prescient and important today than they did in 2007.

Read this one sentence, and you’ll see what I mean.

Leadership can be found in the reliable presence of a parent, the outstretched hand of a friend, the extra effort of a teacher, and the determination by any of us not only to ask the best of ourselves but also to encourage others to live lives rich in accomplishment and love.

Now be sure to read her whole essay – and maybe read it again every week.

Foreword by Madeleine Albright

Foreword by Madeleine Albright

One of the most moving stories to come out of September 11, 2001, involved a passenger on United Flight 93, which went down in Pennsylvania. The passenger, Tom Burnett, called his wife from the hijacked plane, realizing by then that two other planes had crashed into the World Trade Center.

“I know we’re going to die,” he said. “But some of us are going to do something about it.” And because they did, many other lives were saved. Since that awful morning, the memory of their heroism has inspired us. It should also instruct us.

The reason is that when you think about it, “I know we’re going to die,” is a wholly unremarkable statement. Each of us could on any day say the same. It is Burnett’s next words that were both matter-of-fact and electrifying. “Some of us are going to do something about it.”

Those words convey the fundamental challenge put to us by life. We are all mortal. What divides us is the use we make of the time and opportunities we have.

Another way of thinking about the same question is to consider the recent discovery of similarities between the genetic code of a human being and that of a mouse. We are 95 percent the same. Perhaps each night we should ask ourselves what we have done to prove there is a difference. After all, mice eat and drink, groom themselves, chase each other’s tails, and try to avoid danger. How does our idea of “have a nice day” depart from that?

It is possible, of course, that we are all so busy using time-saving devices that we don’t have time to do anything meaningful. Or we may have the right intentions, but instead of acting, we decide to wait—until we are out of school, until we can afford a down payment on a home, until we can finance college for our own children, or until we can free up time in retirement. We keep waiting until we run out of “untils.” Then it is too late. Our plane has crashed and we haven’t done anything about it. We have lived our lives, but we have not led.

As the poems and commentaries in this volume attest, leadership is a concept with as many facets as life itself. The book’s thesis, though, is that true leadership comes not from the sound of a commanding voice but from the nudging of an inner voice—from our own realization that the time has come to go beyond dreaming to doing.

The question of course is, What to do? The answer must be determined by each of us in accordance with our own circumstances and values, but the past has given us clues.

Leadership is found most often in simple acts of self-expression, when conscience overcomes reticence and we make our presence known by challenging a falsehood that has been advertised as truth, calling injustice by its name, stopping to help another, or on one memorable occasion, daring to take a seat at the front of a bus.

We think of great leaders as famous, and some of them are, inspiring others to follow: Gandhi kept on his desk a bronze casting of Abraham Lincoln’s hand; Martin Luther King Jr. carried in his heart Gandhi’s doctrine of creative nonviolence; generations of community activists have found their calling in response to the summons of Martin Luther King Jr.

There are, however, many more models created by people whose names will never be etched in marble or memorialized in a book. Leadership can be found in the reliable presence of a parent, the outstretched hand of a friend, the extra effort of a teacher, and the determination by any of us not only to ask the best of ourselves but also to encourage others to live lives rich in accomplishment and love.

Not every leader marches at the head of a band.

As America’s secretary of state, I was privileged to represent my country in nations across the globe. I had many meetings with high officials in fancy offices, but these were not the meetings—or the leaders—I remember the most.

The people I will not forget are those I encountered in refugee camps and rehabilitation centers, in health clinics and safe havens for trafficked women and girls. These are the places where human character undergoes its toughest tests and where most people live on less money each day than many of us spend for a cup of coffee.

Among those I visited were women in Africa infected with HIV/AIDS. Because of the infection, they were shunned by their families. Other women refused to be tested to avoid being shunned, while many of the men refused to believe anything they were told about the disease or how it could be prevented. I held in my arms the children of such parents—children born with HIV and already dying from it. Some say the struggle against this disease is hopeless, but it is not.

For I also saw educators and health care workers fighting to stop the dis- ease through truth-telling campaigns that were unafraid to shock. We know that such efforts make a difference, for they have already reduced infection rates and saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

While in office, I visited with children in Sierra Leone who had lost limbs in that country’s bloody civil war. Some of the children were too young even to know what they were missing. I remember especially a little girl named Mamuna who wore a red jumper and who—while we talked—used her one arm to play with a toy car. Mamuna was three years old. I could not help but ask how anyone could have used a machete against that girl. After all, whom did she threaten? Whose enemy was she? Mamuna was not alone in the camp where we met. There were many others, of all ages, waiting for prosthetics to replace the limbs they had lost.

Yet, if there was self-pity in that camp, I did not see it. If there was anger and bitterness, I did not feel it. What I saw instead were teams of dedicated doctors and volunteers doing all they could to celebrate the gift of life.

I also visited poor neighborhoods and talked to families in impoverished regions from Haiti and Honduras to Burundi and Bangladesh. I saw people who lived a dozen to a room, or half a dozen to a cardboard box; people struggling to survive in crowded neighborhoods where nothing grows except the appetites of small children.

There are those among us who romanticize poverty; others just try not to think about it. But make no mistake, extreme poverty is a jail in which all too many of our fellow human beings are sentenced for life. Helping them to escape is not simple, but we have learned that progress can be made through a combination of giving more, teaching more, expecting more, empowering women, and developing more equitable rules for labor, investment, and trade. Above all, we need leaders who will not accept that misery and deprivation are inevitable, for failure to act to ease suffering is a choice, and what we have the ability to choose, we have the power to change.

We have learned that leadership on behalf of right can achieve miracles, or at least bring the impossible within reach.

Opportunities for leadership are all around us. The capacity for leadership is deep within us. Matching the two is this book’s purpose—and all the world’s hope.

Leave a Comment